The story of minutiae part I

A three part story told by Martin Adolfsson

The story of minutiae began in a packed and poorly ventilated room at New Museeum’s incubator program, NEW INC, in New York City in late 2014. Members of the incubator had been invited to participate in an upcoming art & tech festival. The festival organizers encouraged us to harness “Big Data” in new, innovative ways. The term “Big Data” seemed to be on everyone’s lips around this time. It was held as this panacea about to revolutionize society. A new way to use algorithms to turn complex problems into overtly simplistic solutions that could be explained in nice-looking graphs and charts.

Luckily, I discovered that I shared the same skepticism about the “revolutionary” part with the guy sitting next to me. His name was Daniel, a fellow artist and member of the same incubator. As we got talking, we found a common interest in the less quantifiable aspects of life—the subtle nuances that are seemingly insignificant but essential to our lived experience. We began discussing creating a project to capture these types of moments by placing cameras in weird, overlooked spots that most people wouldn’t think to document.

“Our eureka moment came with the decision to slice time into minutes rather than hours, offering users a daily minute to document their lives.”

Soon, we realized that the obvious solution already existed: the millions of camera phones people carried around in their pockets. Instead of buying a bunch of cameras, we decided to build an app that would allow anyone with a smartphone to capture these types of in-between moments. Exactly how it would work wasn’t very clear. How would we know when an in-between moment occurred for someone? Our eureka moment came with the decision to slice time into minutes rather than hours, offering users a daily minute to document their lives. The long-term results would be an accurate reflection of their life where the vast majority of the images would be in-between moments.

We decided to name the project “Little Data” as a counter-reaction to Big Data. Since none of us had any experience coding or building apps, we asked another member of the incubator if he’d be interested in building a prototype to test the concept. A few weeks later, we had a very barebone prototype that could notify the user to take a photo and save it to the camera roll.

“We decided to name the project “Little Data” as a counter-reaction to Big Data”

We managed to convince a few friends around the world to install the prototype and, at the notification, snap a photo and email it back to us. To be honest, we didn’t really expect much. Most of the people we talked to about documenting the “in-between” moments of life laughed at us and asked why they would take photos of their kitchen sink, their morning commute, or some other boring moments. To be fair, this was 2015, and the general consensus was that social media was a great way to bring people closer together. Instagram had only been around for a few years, and it was mainly a fun photo-sharing app; its true impact on culture and society was still not obvious.

“Most of the people we talked to about documenting the “in-between” moments of life laughed at us and asked why they would take photos of their kitchen sink, their morning commute, or other boring moments.”

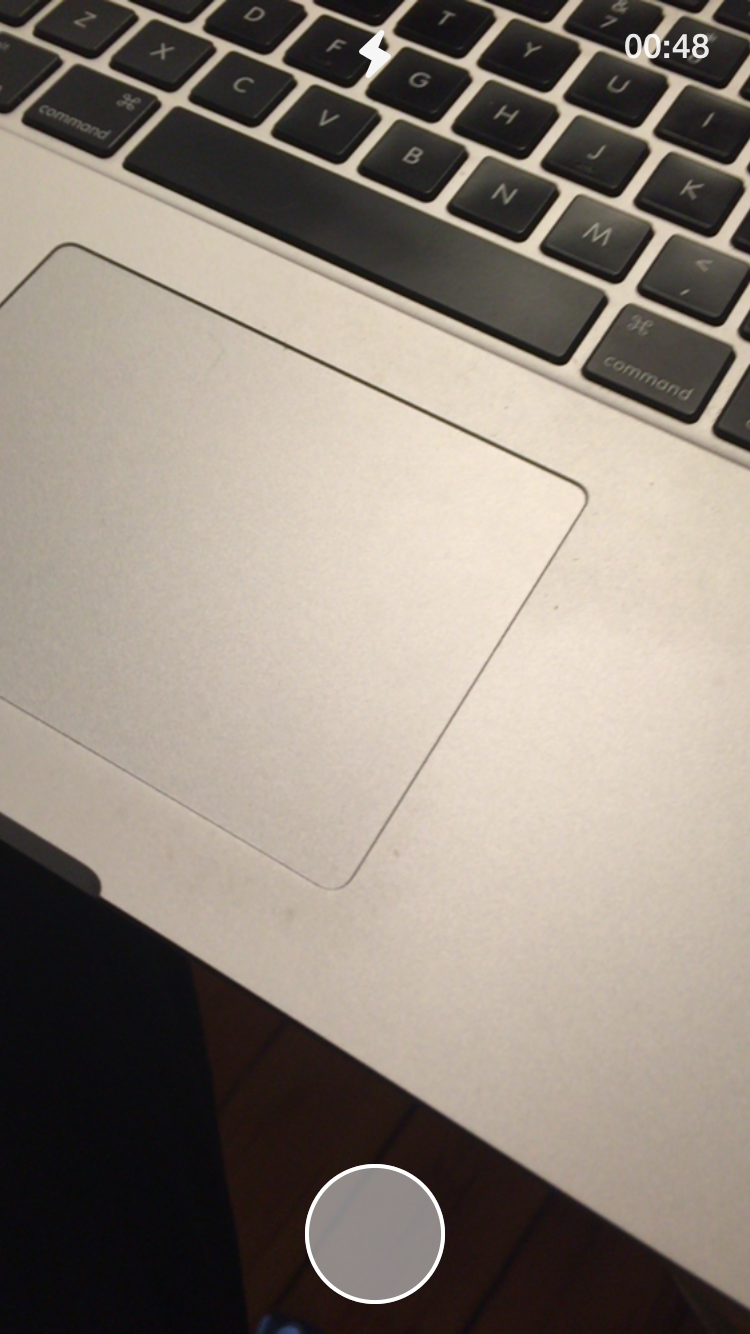

To our surprise, our inbox started to fill up with photos of people being stuck in traffic in LA, having an evening snack in Sao Paulo, and hundreds of small, seemingly insignificant moments. The photos had a deeply personal quality to them as if you got a glimpse of someone's actually real life that you weren’t really supposed to see. They were the absolute opposite of the perfectly manicured moments that you'd see in your Instagram or Facebook feeds. This was a receipt that the concept actually worked. Not only were the photos unique, but our friends also kept using the prototype long after the initial test period was over.

Some of the very first moments captured with “Little Data”.

Now came the big question: how do you turn a barebones prototype into a working smartphone app that people outside of our group of friends would actually use? We began reaching out to software developer studios for quotes. But after a few meetings, we realized we had a big problem. We didn’t have anywhere near the money required to build an app like this. The obvious thing would perhaps have been to go and seek funding from venture capitalists. After all, we wanted to build an app, and that’s the type of stuff investors love.

“How do you turn a barebones prototype into a working smartphone app that people outside of our group of friends would actually use?”

However, we had no intention of monetizing the concept—this was an art project and a counter-reaction to generalties, not the other way around. The app was designed so that users would spend as little time as possible on it—no infinite doom scrolling, profiles, or likes. The color scheme was all in grayscale to prevent that sweet dopamine hit that all the platforms worked so hard to monetize.

Instead, we began to apply for art grants to help build the project. However, no one wanted to fund an app project. To most people, apps equal startups, and they only fund “real” art, not the stuff you have on your phone. Weeks went by, then months, and eventually, a full year passed without any real progress, and it began to feel like the project was dead…. until one day.